Artist Alfred Leslie's film The Last Clean Shirt with subtitles by poet Frank O'Hara (who lifted some of them from Alfred Leslie) was first shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1964.

From Tate Modern (who screened the film this past Wednesday, 24 June 2009):

In a letter to his friend and collaborator, the poet Frank O'Hara, Leslie writes: 'We will shoot for two SEPERATE LEVELS on the film. One is the VISUAL, the other the HEARD & the spectator will be in TWO places or more SIMULTANEOUSLY. NOT AS MEMORY BUT AT THE SAME MOMENT. PARALLELISM! MULTIPLE POINTS OF VIEW!'

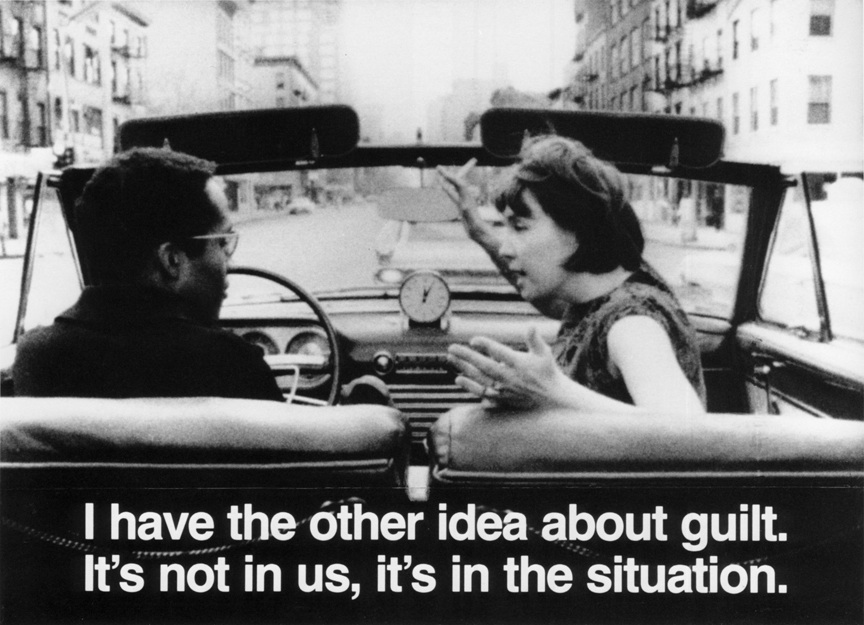

It is a blueprint for The Last Clean Shirt in which a man and a woman take a car ride through the streets of downtown Manhattan. A clock on the dashboard foregrounds the fact that the film is a single shot. The woman speaks in double-talk Finnish, interpreted by the beautiful and brilliant story told via O'Hara's subtitles that run throughout. (more)

From NYS Writers Institute:

The Last Clean Shirt is a rarely-screened film that has become even more intriguing and thought-provoking with the passage of time. A young black man and white woman get in a car at Astor Place, tape an alarm clock to the dashboard, and start driving around as the woman yaks in an unknown language. This action is repeated three times, each segment featuring a different subtitled stream-of-consciousness narration by poet Frank O’Hara. Predating the rise of structural filmmakers like Michael Snow and Hollis Frampton by several years, Leslie’s film anticipates later avant-garde interest in the limits of cinematic form. Snubbed by critics and booed by audiences . . . at the 1964 New York Film Festival, The Last Clean Shirt was considered audacious and excessive in its day. During a run at the New Yorker, one crowd hounded the owner of the theater so badly that he was chased out of the building and hid in a dumpster. (more)

From Jacket 23:

The Last Clean Shirt was even more avant-garde or visionary than critics were able to see at the time: it is not merely a film but a new form of work of art, a new literary object, in the wake of the simultaneous poem (Blaise Cendrars). One might then wonder how the film goes beyond simultaneity in the mapping of a new artistic space created between images and words . . .

The film betrays the concerns of the painter: lines, planes and dimensions are carefully organized on the screen and enter a field of tension. The spectator can see vertical lines: the characters, the street, the buildings, the windshield frame and the hands of the clock. Horizontal lines also come into play: the subtitles, the upper part of the seats and of the windshield and a series of small horizontal lines can be seen on different parts of the screen.

Circularity also finds its place with the clock, the wheel and various buttons on the dashboard of the car. There seems to be no depth, no relief whatsoever on the screen. It is as though Alfred Leslie went back to the early years of cinema to show us that what we take for granted i.e. verisimilitude, lifelikeness, 3-D relief are but a construct, an illusion. (more)

Alfred Leslie (link)

Frank O'Hara (link)